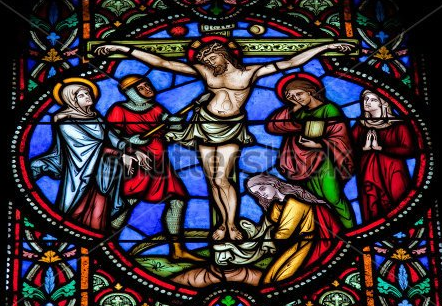

“Is there something more in his being crucified than if he had died some other death?” asks the Heidelberg Catechism. Answer: “Yes, for by this I am assured that he took on himself the curse which lay upon me, because the death of the cross was cursed of God” (Q. 39). “He hung upon the tree to take our curse upon himself; and by this we are absolved from it” (Calvin, Catech. of the Church of Geneva; Gal. 3:10). Hanging on a tree was purposefully intended to expose the corpse to ultimate disgrace (Deut. 21:22–23). “A form of death had to be chosen in which he might free us both by transferring our condemnation to himself and by taking our guilt upon himself. If he had been murdered by thieves or slain in an insurrection by a raging mob, in such a death there would have been no evidence of satisfaction,” but by his arraignment as a criminal we know that as one innocent he voluntarily “took the role of a guilty man” (Calvin, Inst. 2.16.5). That he hung between thieves fulfilled the prophecy that “he was numbered with the transgressors. For he bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors” (Isa. 53:12; Mark 15:28; Calvin, Comm. 8: 130). Even on the cross he continued his ministry of pardon and reconciliation (Gregory of Nazianzus, On Holy Easter, Orat. 45.24).

The Cross

The sign on the cross read: “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews” (John 19:19). The religious authorities protested, but Pilate insisted. Pilate’s inscription was viewed by the church as an ironic declaration of Jesus’ true identity (Origen, Comm. on Matt.130). “These three languages were conspicuous in that place beyond all others: the Hebrew because of the Jews who gloried in the law of God; the Greek, because of the wise people among the Gentiles; and the Latin, because of the Romans who at that very time were exercising sovereign power of many, in fact, over almost all countries” (Augustine, Tractates on John 117.4) The classic exegetes stood amazed at the ironic depths of the layers of the narrative (Leo I, Sermon 55.1). Those who most radically symbolized the sin of the world through their very act of absurd rejection played bit parts in the story of the salvation of humanity. The very rabble who were rejecting his testimony were at the same time paradoxically offering up the victim who would redeem. While they cried “Crucify,” he prayed “Forgive” (Augustine, Sermon 382.2). He who knew what was in the human heart prayed for his persecutors: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34; Pope, Compend. 2:162). Christianity transformed the symbolic significance of crucifixion. Until the day of Jesus’ death, it had been a demeaning symbol of political repression. Its distinctive shape—“the four arms converge in the middle”—became a symbol of “the one who binds all things to himself and makes them one,” wrote Gregory of Nyssa. “Through him the things above are united with those below, and the things at one extremity with those at the other. In consequence it was right that we should not be brought to a knowledge of the Godhead by hearing alone; but that sight too should be our teacher” (ARI 32). The cross teaches those “rooted and established in love” “to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ” (Eph. 3:18). “Make this sign as you eat and drink, when you sit down, when you go to bed, when you get up again, while you are talking, while you are walking; in brief, at your every undertaking” (Cyril of Jerusalem, Catech. Lect. 4.14). “He came Himself to bear the curse laid upon us. How else could He have ‘become a curse,’ unless He received the death set for a curse? and that is the Cross,” Athanasius reasoned. “It is only on the cross that a man dies with his hands spread out” to encompass humanity (Athanasius, Incarn. of the Word 24)!

Oden, Thomas C.. Classic Christianity (Systematic Theology) (pp. 393-394). HarperCollins.